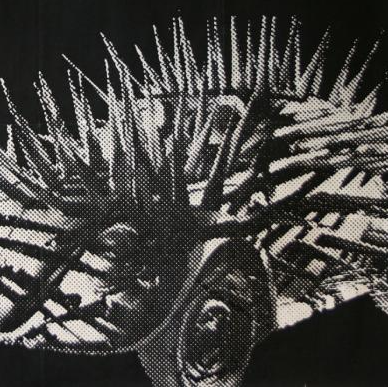

Boom

In the margins between genius and madness, there is only 'BOOM'.

UK poster | Universal Pictures /

Rank Film Distributors

1968 — UK/USA

A production of UNIVERSAL PICTURES, WORLD FILM SERVICES and MOONLAKE PRODUCTIONS, presented by UNIVERSAL PICTURES

Cast: ELIZABETH TAYLOR, RICHARD BURTON and NOËL COWARD, with JOANNA SHIMKUS and MICHAEL DUNN

Director: JOSEPH LOSEY

Producers: JOHN HAYMAN and NORMAN PRIGGEN

Screenplay and Original Work by: TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

Editor: REGINALD BECK

Cinematography: DOUGLAS SLOCOMBE

Production Designer: RICHARD McDONALD

Art Director: JOHN CLARK

Music: JOHN BARRY

© Universal Pictures

On a private island off the Italian coast, the richest woman in the world and habitual widow, Mrs Sissy Goforth (a much too young for the part Liz Taylor), holes herself up dictating her memoirs to her put-upon secretary while being generally rather a bitch to anyone who gets not so much in her way as vaguely in her proximity. Onto this island arrives the mysterious young poet Christopher Flanders (a much too old for the part Richard Burton), a man with a penchant for getting in with old ladies just before they cark it. When he proceeds to crash her little kingdom, she does her ultimate bad hostess routine and yet he won’t seem to leave.

Adapted by Tennessee Williams from his own play The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore;* a flop which originally received some poor reviews and closed on Broadway after a meagre 69 performances (*fnar*), only to be revised and revived as a more kabuki-ish style work (complete with kuroko) which was similarly poorly reviewed and axed after five performances; Boom was a not inconsiderable flop. Given the history of the stage production, one wonders what they expected. Director Joseph Losey (best known perhaps for his collaborations with Harold Pinter, particularly The Servant (1963) and The Go-Between (1971)) apparently claimed to have been the only person to lose money with Burton and Taylor headlining, though quite how true that actually is I don’t know. Nonetheless, the film’s gone on to have a second life as a camp classic, championed most (in)famously by John Waters.

As you might have noticed from the premise, the plot of the piece is a lot more abstract than one might expect given the sort of work for which Williams is best known; his sexually charged Southern Gothic melodramas, stereotypically about fragile women who people are just itching to have sectioned, faded belles refusing to age gracefully or volatile dangerous men with some shocking secret, or you know a combination thereof (yes, yes, this is all very reductive, I know). To be fair, this also describes this to some degree, but the conflict is, on a surface level at any rate, more prosaic. More in line with theatre of the time, the bizarre conflict gets more symbolic, and the results when put onto the screen are… odd. The thing isn’t one of those films straight-up the play; it actually feels like it makes quite good use of what the change in medium allows; rather it feels stagey in a decidedly different manner.

The casting deserves special mention. Taylor and Burton were, by most accounts, quite drunk for much of the production; that’s probably not much of a surprise to anyone reading; and reportedly Losey was hitting the bottle pretty hard at the time too. This perhaps is rather reflected in the performances. Taylor’s take on Sissy Goforth is at once histrionic and hysteric; a monstrous vision, a larger than life figure, she’s fascinating to watch. It’s absurd, and yet somehow, I can kind of buy it. I don’t recall it ever really being mentioned in the film, but the character is specified in the play as having been in the Follies (the Ziegfeld, presumably), with all that entails. (If I had to guess, presumably as Taylor was only in her mid-thirties at the time and thus too young to have been a Ziegfeld girl, someone decided that it’d be confusing to keep that in there, assuming you’re taking everything on screen quite literally.) The part was originally written with Tallulah Bankhead in mind (although she didn’t originate the role on stage) which might give you an idea as to how different Taylor is casting wise, though really it seemed unlikely that Universal would have bankrolled the film with an older actress. While we were into the post-Baby Jane ‘oh, golden age actresses can still draw a crowd’ era, Bankhead didn’t really do all that many films in general and presumably wouldn’t have had as much of a pull as Bette Davis or Joan Crawford et al,** and it’d probably have been a hard sell getting most of those to play a mutton-y old harridan who refuses to look death in the eye. (It seems like Davis probably would have, but given the time period, she was likely busy playing a mutton-y old harridan who refuses to look death in the eye in The Anniversary instead.) Burton, meanwhile is too old for her sparring partner; played on stage by a young Tab Hunter, Williams’ text very much plays up his comparative youth. That said, he also describes him thusly:

He has the opposite appearance to that which is ordinarily encountered in poets as they are popularly imagined. His appearance is rough and weathered: his eyes wild, haggard: He has the look of a powerful, battered but still undefeated, fighter.

Williams, 67

It’s probably an exaggeration to describe the aging Burton as seeming like a ‘still undefeated fighter’, but there’s a certain method to the madness. Taylor is an embittered but somehow naïve old crone, while Burton is the optimistic but somehow world-weary youth. Symbolism, what, what. While Taylor’s hams, Burton goes quite the opposite, remaining on a perfectly even keel regardless of the lunacy surrounding him. And lunacy there is, I assure you. Wait ‘til you see how Mrs Goforth dresses for dinner.

I should also mention that we have Noël Coward as the ‘Witch of Capri’, Sissy’s quasi-friend, a role originally written for a woman and by most accounts originally offered to Katherine Hepburn here; reportedly she was insulted to have been asked. Coward seems to be relishing the opportunity to be a massive bitch on screen and gets some of the most outrageous lines, including some stuff about women’s genitalia sufficiently vile that the incongruity of him saying it with his trademark plummy affectation renders it bizarrely hilarious. Despite getting listed with Burton and Taylor, his role is very much supporting, yet it’s all memorably strange. But indeed, with the loosening of the production code, it seems Williams was free and more than willing to engage in a bit of vulgarity, with Coward and Taylor tossing about some eminently quotable insults.

The film’s production design is similarly striking; the Sardinian vistas are obviously stunning, and the recreation of the whitewashed villa in the studio is impressive, but the film’s commitment to non-naturalistic visuals is key, occasionally drifting into a look more reminiscent of expressionist films of yore. Ultimately there’s a lot about the film that just plainly shouldn’t work; the bizarre casting, the excessive acting, the extravagant designs, the lack of any real drive to the plot, the idiosyncratic and oft-vulgar script, the general horribleness of the characters, the incessant metaphysical and philosophical ramblings, the stagey artificial style; by rights, the film should be legitimately terrible, and yet it all coalesces into something quite wonderful, quite unbelievable, and, in some ways, quite perfect. A dreamlike cacophony. It’s impossible to imagine it any other way. …Incidentally, Tennessee Williams declared this to be the best film of his work. So, yeah.

*Supposedly the title was changed because it was too long for a marquee, though presumably it managed to fit on one at theatres, so seeing as this was the days before multiplex cinemas were common, one has to wonder quite how true that is.

**In case you were wondering, she did get in on the psycho-biddy craze though. Her last(‑ish) film was Hammer’s 1965 effort

Fanatic (her actual last film was a voice in the part-animated

The Daydreamer (1966); she’s the witch in the

Little Mermaid segment). She did appear in some TV stuff later than either though; perhaps most famously a pair of episodes of

Batman in '67 as the villain of the week.

Surprisingly enough, at time of writing, I can't find Boom on any streaming service, not does it seem to have a JustWatch page for me to conveniently link to. Sorry. Alternatively, physical copies are reportedly available for rent via Cinema Paradiso.

The film has an 12 rating these days, with the BBFC claiming it to have "moderate language and violence", down from an X back in the day.

Sources

Williams, T., 1964. The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore, in Suddenly Last Summer and Other Plays (pp.53-151). London: Penguin (2009).