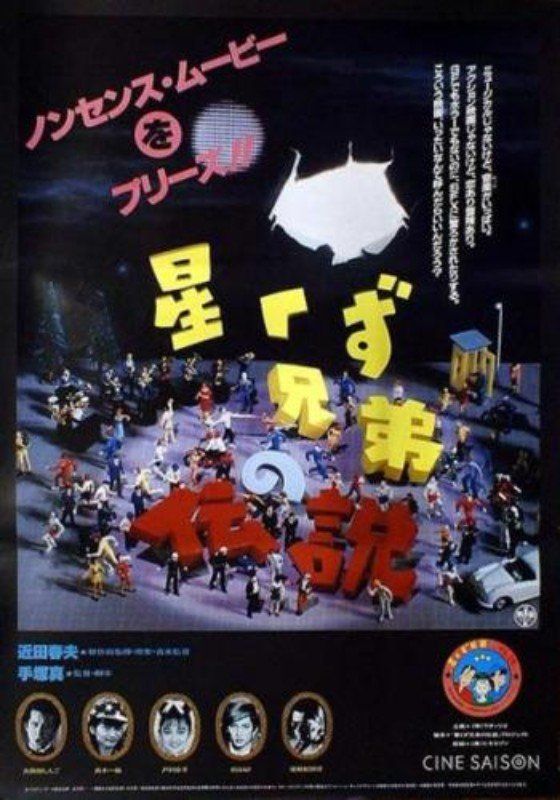

The Legend of the Stardust Brothers

The Tragical History and Most Deserved Deaths of the Stardust Brothers

Japanese poster | Cine Saison

1985 — Japan — Hoshikuzu kyōdai no densetsu

Presented by HARUO CHIKADA

Cast: SHINGO KUMADA, KAN TAKAGI, KAZUHIRO WATANABE, SENKICHI ŌMURA, AKIO YOKOYAMA, NOBORU MITANI, NAKAO SUNPLAZA, TAKO and KIYOHIKO OZAKI with KYOKO TOGAWA and ISSAY

Director and Writer: MAKOTO TEZUKA†

Producers: EIICHI TAKAGI, TAKASHIGE ICHISE, KŌICHI SUZUKI and KATSUNORI HARUTA

Executive producer, and Music and Story by: HARUO CHIKADA

Editors: MARI KISHI and MAKOTO TEZUKA

Cinematography: EIICHI ŌZAWA

© [Kinema Junpo DD]

† In this film, his name is romanised in the credits as the more standard ‘Makoto Tezuka’, but he seems to favour the spelling ‘Macoto Tezka’ now, so I’ll be using that in the actual review.

This article is based around the version from the 2018 re-release (to tie in with the sequel/remake/whatever it is), the considerably easier version to see. Apparently Tezka made some tweaks, but I can't find much specific as to what they might be.

The Legend of the Stardust Brothers was the first film as a professional by Macoto Tezka; son of Osamu Tezuka, the ‘father of manga’, creator of Astro Boy (1952-68), Kimba the White Lion (1950-54) and Black Jack (1973-83), amongst many, many, MANY others; though not really his first feature length effort. At least three of his student films, Moment (1981), Shelly and SPh (both 1983) crack the hour mark, and so definitely qualify as ‘feature length’ by several film organisation standards.* The first of which at least reportedly saw play at the Berlin Film Festival, and became a minor hit on the university circuit in Japan. Its popularity lead to this film, made while he was still at university. Reportedly, musician Haruo Chikada was a fan and having a few years earlier make a concept album whose conceit was that it was a soundtrack to a film that didn’t exist, decided to get Tezka on board to make said film a reality.

So, what is this The Legend of the Stardust Brothers about? Well… the eponymous Stardust Brothers (despite the Japanese title referring to them as ‘Hoshikuzu Kyōdai’, within the film they’re always referred to by the English) are a washed-up pop duo, but all of two years ago they were the hottest band in Japan. And so, at a cabaret, they recount to the terminally unimpressed audience their rise and fall. Would-be city pop type Shingo and would-be punk type Kan are bitter rivals in the music scene (or maybe not, certainly one is a lot more invested in their rivalry than the other) who find themselves scouted by a highly powerful, highly shady management company, the boss of which (Kiyohiko Ozaki) will sign them both for a half-million dollars provided they team up as a duo, claiming that they’re definitely the long lost twin sons of a musical genius, separated at birth, and musical talent is genetic, don’t you know? It’s both or neither though; presumably each having half their father’s DNA, the pair of them will thus be equal to one of their father. Well, the money’s good, so… the marketing machine rolls on, but their sense of rivalry eventually results in friction and erratic behaviour. The entertainment industry is however a great influence on the public and their perception of the world, and the boss finds himself paid by the government to ditch the brothers whose bad behaviour is wrong for Japan’s future and instead promote Kaoru Niji (ISSAY), the son of a prominent politician, who will sing nice songs and have a squeaky-clean public image. Oh, yeah, also his dad’s Hitler. It’s that sort of film.

The original album was reportedly inspired by Brian de Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise (1974), which if you’re unfamiliar, you might be able to guess from the title is some kind of campy rock musical version of Phantom of the Opera (predating the Andrew Lloyd Webber one by over a decade and the considerably less popular Ken Hill one by a couple of years), albeit with some Faust and Dorian Gray thrown in for good measure; the Phantom analogue is a songwriter (William Finley) manipulated by a record producer (Paul Williams), who incidentally has sold his soul to the devil for unholy record producing success. Jessica Harper and Gerrit Graham are in there as the Christine and Carlotta counterparts respectively, and Rod Serling provides narration. Very big in Winnipeg. No, really, look it up. Anyway, this bleeds into the film incarnation of Stardust Brothers; rather openly in fact, with the end credits dedicating the thing to Winslow Leach, the eponymous phantom; along with things like The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and Tommy (1975), with its examination of the fantastically seedy world of the business we call show, and a glimpse into sub-culture not all that often seen in Japanese film. Tezka acknowledges that the film’s rather blasé approach to things like drug use and queer culture was largely inspired by the sorts of western films that he and Chikada were into; while, as he says, such things do obviously exist in Japan, typically the film industry doesn’t really portray them, or at least it didn't in the '80s. It is admittedly rather surprising to see a Japanese film with a scene of one of the leads doing coke, particularly in such a casual way rather than as some especial major point; while Shingo’s substance abuse factors into the plot, it’s treated much more generally than about one specific substance. The film actually lays its cards fairly bare in the opening, during the Brothers’ opening act, they’re conveniently enjoying their vices to the consternation of their audience and the chagrin of the cabaret club’s management. Their take on their rise and fall is perhaps less than reliable. On the other hand, the film does make some definite inside baseball allusions to the music industry; the brothers’ Svengali has some curious parallels to an influential figure in the Japanese pop industry… the allegations (or not, as the courts certainly seemed to rule that the bit that should have been but wasn’t damaging was true) surrounding whom are hardly unique in the music industry at large.

Despite the talk of Phantom of the Paradise and that, Kim Newman makes the observation that apropos comparisons might perhaps actually be the 1982-ish Forbidden Zone** (also some stuff about Shock Treatment (1981), the Rocky Horror team’s even cultier follow-up, that I’m not quite sure works in the comparison he seems to be making, though on a different tack lines could be drawn with that film’s scathing media satire, even if the media being targeted is different; the shenanigans in that film’s production was more to do with a Screen Actors Guild strike than not having the money per se). Aside from the film’s cult credentials in Japan (which, I mean, it does share with Paradise and Rocky Horror and co.), I assume the idea there being Stardust Brothers’ similar mixture of animation, bizarre set pieces, and low, low production values with a fairly thin plot (though Tezka’s film frankly has a lot more of one of the those, and honestly probably more of a budget as well; it has actual location shooting!). The film is all rather low rent and frequently amateurish looking, which does make sense given its background, while also generally being rather ambitious in what it’s trying to achieve. Reach extending grasp, or whatever, but it’s nevertheless brimming with fun ideas and visual flair as they go for the creative solution to problems. Quite what the budget was, I can’t find out, but apparently major studio Toho scoffed at the proposal, professing that it’d cost 30 million (dollars, one assumes; ¥30m was about $125k in the mid-eighties, so doesn’t seem like they’d be able to use ‘expense’ as a reason to refuse in that case) to do what they were asking,*** so we can assume quite a bit less than that. The money was actually gotten from Seibu Department Stores rather than an established film company, and there’s a whole lot of pulling in favours from friends and family. The thing’s bursting with enthusiasm, if not polish.

*The British and American Film Institutes and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences all deem any film longer than 40 minutes to be a feature. This isn’t really a universal standard, mind you. The American Screen Actors Guild demands they be at least 75 minutes, while the Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée apparently requires they be a 35mm film “longer than 1600 metres” (which at your standard 24 fps exhibition means about 58 and a half minutes). This is all per Wikipedia, and they don’t have a source for that CNC claim, so take as you will.

**Forbidden Zone is copyrighted 1980, but, per the director, didn’t see release until ’82. Apparently it was shot over the course of a few years prior to that.

***For comparison, Toho’s 1984 Godzilla movie reportedly cost them about $6.25m. Elsewhere, Akira Kurosawa’s Ran, released about the same time as Stardust Brothers, ran to about $11m, and that was a foreign co-production.

At time of writing, The Legend of the Stardust Brothers is available for rent on Youtube and Amazon, amongst other services. I recommend JustWatch for keeping up with where films are streaming (including this one!). Alternatively, physical copies are reportedly available for rent via Cinema Paradiso.

The film has a 15 rating from the BBFC, citing "drug misuse". It also makes note of the film having flashing images that "may affect viewers who are susceptible to photosensitive epilepsy", so that's something to be aware of.