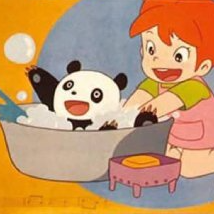

Letter to Brezhnev

'Tefteli' are a type of Russian meatball.

UK poster | Palace Pictures

1985 — UK

A CLARKE/BERNARD production, presented by PALACE PICTURES and FILM FOUR INTERNATIONAL in association with CHARLES CASELTON

Cast: PETER FIRTH, ALFRED MOLINA, ALEXANDRA PIGG and MARGI CLARKE

Director and Executive Producer: CHRIS BERNARD

Screenplay: FRANK CLARKE

Producer: JANET GODDARD

Editor: LESLEY WALKER

Photography: BRUCE McGOWAN

Production design: LEZ BROTHERSTON, NICK ENGLEFIELD and JONATHAN SWAIN

Costumes: MARK REYNOLDS

Music: ALAN GILL

© Yeardream ltd.

Letter to Brezhnev, perhaps unexpectedly, was one of the notable successes of British film in the 1980s. It certainly helped put both Film4 and Palace Pictures on the map (as well as Liverpool as a shooting location) so far as film production went; while neither the first nor the most successful film by either (nor indeed their first co-production; both were involved with 1984’s The Company of Wolves, though Film4 are not credited within the film itself, nor do either company (or their successor-in-interest in Palace’s case)* hold it as part of their catalogue), but it struck a chord with audiences and critics alike at home and abroad. Not too bad, given as a large part of the film was apparently made on a budget of but £50k.

A Soviet ship arrives in darkest Liverpool as a leg on some vaguely defined diplomatic thing. On board, this here ship are, natch, Russian sailors lookin’ for a good time in capitalist hellholes. Elsewhere, not very far away, Elaine (Alexandra Pigg) and Teresa (Margi Clarke) are two working class gals looking for love (or lovin’, at least) in all the wrong places or whatever; the former unemployed, the latter with a chicken gutting job. Ah, the glamourous world of the 1980s. Breaking out of Kirkby for a night on the tiles in the city, they find themselves hooking up with a pair of the aforementioned sailors, Peter and Sergei (played somewhat implausibly by Peter Firth and Alfred Molina respectively), in town for one night only. Fun is fun and all that, but Elaine and Peter click pretty much instantly. She is soon left to ponder if she should pack in this life and run away to Russia to be with her paramour. After all, what has she got to lose?

Predictably, they had some trouble getting the production off the ground, which seems to be the running bit for stuff I talk about here. Would you believe that most companies weren’t big into this premise during the height of the Cold War? I mentioned a little while back that this was one of several films of the era that EMI apparently passed on that proved to be fairly successful for other companies. In this one’s case however, it seems that even the usual suspect that is Film4 was somewhat leery; the initial £50k budget (waggishly referred to by Margi Clarke as being the same as ‘the cocaine budget for Rambo’) came from a private investor (the ‘Charles Castelton’ mentioned in the ‘presents’ credit) with whom Frank Clarke was loosely acquainted; with them and Palace only getting involved after being impressed with the rough unfinished cut. This would seem to suggest both claims of the film’s budget floating about (£50k according to various crew people, £379k according to the BFI (claiming Channel 4 as the source of the info)) are somewhat true. With two-thirds, apparently, done, one wonders if they really needed some six-and-a-half times the initial budget to finish it off, but I guess it’s hard to begrudge them, it’s still pretty miniscule as budgets go. I’d assume a lot of it went on the soundtrack, with Palace reportedly wanting a lot of licensed music for the various pub and club type scenes.

…Continuing the low budget theme, Margi Clarke also posits that you can spot the bits that were shot later, because everyone’s gained weight from being able to afford to eat properly.

Anyway, the film manages quite an admirable aesthetic. The first hour or so, which is to say ‘the romantic bit’, features a non-naturalistic use of light and colour that serve to give the whole affair a dreamy, fairy tale like feel, before things come crashing to the more grim reality in the last act. Economic depression has seldom looked so beautiful. At the same time, it keeps enough reminders of the real world in the seediness and more generally unpleasant sides of its production design. Consider that Teresa spends a good half the film wandering around in her filth splattered white coat from the abattoir. While this obvious serves as a counterpoint to when she does change out of her work garb for her ‘Why, Miss Jones, you’re beautiful’ moment (or a variant thereof, at any rate), it serves as a reminder that life is not, in fact, beautiful. I suppose if I really knew what I was talking about, I could talk about this contrast aesthetic contrast with regards to things like New Hollywood and Cinéma du Look and things like that. But I don’t, so instead you’ll have to draw your own conclusions. It is perhaps worth considering that this kind of aesthetic doesn’t seem out of keeping with contemporary British films such as Mona Lisa, Absolute Beginners and Sid and Nancy (all 1986). Meaning what exactly? Eh, I don’t know. Maybe something about disaffected youth and escapism (or lack thereof) in the times of Thatcher? Hmm… well, if you ignore that only one of those three is set in (wholly) ‘80s. Still, all of those films also involved Palace in some way; the former two being actual in-house productions… they also released two of the first Look films, Diva (1981) and La Lune dans le caniveau (1983) in the UK prior to getting into the production game. Their bread-and-butter, I guess.

A key point however is that, despite its romantic comedy framework which honestly works pretty well, the film is not actually about the romance, or rather the romance is not the key thrust of the film. The film’s primary interest lies more in the devastation that much of the country was facing at the time; the mass unemployment, the gutting of services, and the general apathy with which these issues were met by those in charge. The charitable reading that I’ve seen of government policy at the time was that there was this idea that those who benefitted would in turn, rather than keep their wealth to themselves, engage in philanthropy and private charity and all that which would keep the world ticking along in a fashion satisfactory to everyone, à la Victorian times. Of course, this is nonsense and, at best, speaks to ill-conceived nostalgia for a past that never really existed and essentially no one was old to have experienced even if it had; for all the nation’s great philanthropists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, who usually got their money through means that could euphemistically be called ‘problematic’ (a fact that has recently caused monocles to pop), it’s pretty established that poverty and suffering within Britain was still rife and there are numerous contemporary essays which posit that private charity was just papering over the cracks caused by the same private enterprise that enabled said charity. Back on the subject of the 1980s, this all assumes you’re being generous in interpreting the government’s motive. It seems like a big ask. For all the reports of food shortages, censorship and myriad other forms of oppression and general crushing misery of life on the other side of the iron curtain with the implication that one definitely doesn’t see such things in the west, trust us, suffice to say, people did. The film avoids doing much to suggest that things are better in the Soviet Union, its lack of examination on the Russian side of the equation being a point of contention with many, more contemplation of whether, for many people, could it really be worse than what they have now?

Incidentally, the date on the eponymous letter when it makes its appearance is the 22nd of January, 1985. Leonid Brezhnev died on the 10th of November, 1982. None of the plain people of England with whom Elaine consults are apparently aware of who the Soviet head of state actually is. (It was Konstantin Chernenko as of the date of the letter, though he was dead himself by the time the film came out; the film hedges its bets and has a generic figure for the brief scene of receiving the letter.)

* It’s MGM, in case you were wondering. I suppose more properly it’s Orion Pictures, but, you know, MGM owns them.

At time of writing, Letter to Brezhnev is available to rent off of Amazon and the BFI Player, amongst other services. I recommend JustWatch for keeping up with where films are streaming (including this one!). Alternatively, physical copies are reportedly available for rent via Cinema Paradiso.

The film presently has a 15 rating (last rated 2003), the BBFC citing “strong language and sex references”.