The Secret of Moonacre

"Intimacy with good example."

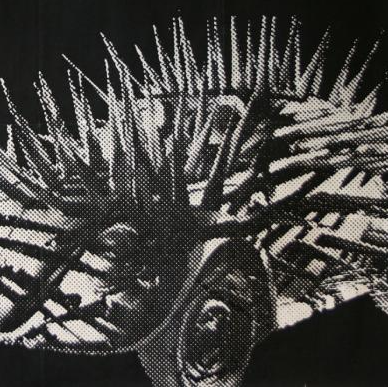

UK poster | Warner Bros.

2008 — UK / Australia / Hungary / France

A FORGAN-SMITH ENTERTAINMENT / SPICE FACTORY / LWH FILMS / EUROFILM STUDIO / DAVIS FILMS production in association with GRAND ALLURE ENTERTAINMENT and ARAMID ENTERTAINMENT, presented by WARNER BROS PICTURES, VELVET OCTOPUS and the UK FILM COUNCIL

Cast: IOAN GRUFFUD, TIM CURRY, NATASCHA McELHONE, JULIET STEVENSON and DAKOTA BLUE RICHARDS

Director: GABOR CSUPO

Producers: JASON PIETTE, MICHAEL L. COWAN, SAMUEL HADIDA, MONICA PENDERS and MEREDITH GARLICK

Executive Producers: DAVID BROWN, SIMON CROWE, SIMON FAWCETT, VICTOR HADIDA, MATTHEW JOYNES, ALEX MARSHALL, JENNIFER SMITH and KASPAR STRANDSKOV

Screenplay: LUCY SHUTTLEWORTH and GRAHAM ALBOROUGH

Original work: ELIZABETH GOUDGE

Editing: JULIAN RODD

Cinematography: DAVID EGGBY

Production design: SOPHIE BECHER

Art direction: BILL CRUTCHER, MÓNIKA ESZTÁN, GARY JOPLING and GABRIELLA SIMON

Costumes: BEATRIX ARUNA PASZTOR

Music: CHRISTIAN HENSON

© UK Film Council / Eurofilm Studio / Davis Films / LWH Films

13-year-old Maria Merryweather (Dakota Blue Richards) has a problem. Her father is quite dead, and also I guess her mother is too but they don’t dwell on that one. This is, of course, par for the course for children’s fantasy. Also he was broke and the will affords her basically nothing, except for a book about the old timey legend of the Moonacre Valley. Which is to say that once upon a time, a maiden of the De Noir clan who was pure of heart and all that jazz was bestowed upon by the moon a set of magical pearls. This woman, dubbed the Moon Princess, is set to marry into the Merryweather clan, and upon her wedding day presents the two families with her enchanted chunks of oyster barf, informing them of the vaguely defined great power entrusted unto them. However, both sides are immediately consumed by greed, lust for power, you know the drill. And so begins a blood feud that has lasted many generations. As luck would have it, she’s been sent to live with her raging misogynist uncle, Sir Benjamin Merryweather (Ioan Gruffud), at his isolated, crumbling estate in the Moonacre Valley. In the keep on the other side of the surrounding forest, and lurking around therein, are the De Noirs, led by the ironically quite heartless Coeur de Noir (Tim Curry), eking out a living now as bandits. Each side convinced the other has the pearls, the feud rages on. It seems however that the Moon Princess, sufficiently distraught by the families’ behaviour, laid down a curse upon them; should they fail to reconcile (and, you know, renounce their desire to use the Macguffin for personal gain), then in 5000 moons time, the valley will we plunged into ‘eternal darkness’, which apparently actually means the moon will crash into the valley Majora’s Mask style and kill everyone (and presumably destroy the world). As you might expect, this deadline is actually quite imminent, Maria reckons. No one will listen to her though, ‘cause she’s just a silly girl or whatever, so she’ll just have to take matters into her own hands, at least until everyone else involved gets over themselves.

I haven’t read The Little White Horse (1946). In truth, I’d never actually heard of it, although it seems like it’s actually a fairly major slice of children’s fantasy fiction and is held in high regard by a lot of readers, particularly women who read it in their youth. In fact, that might be the key there as to my lack of knowledge on the subject. It’s almost certainly something that would’ve gotten pigeonholed as a girl’s story, what with basically everything aimed at children ending up divided along gender lines, very little of that sort of thing saw its way into my orbit; the furthest on that front at the all-boys school I attended was a couple of The Worst Witch books floating about the classroom bookshelves and the odd girl centric extract or story in the readers. Of course, for all I know, this could’ve cropped up as one of said extracts, I don’t remember for the life of me. This is all moot anyway as this is by all accounts a very loose take on the source material. As in ‘large quantities of the character relationships are different’ loose. Oh, yeah, and also those big world ending stakes are added in for the film. Surprisingly there’s less moaning about its creative liberties online than I expected, with most people into the source material seeming to take the approach that it’s a decent enough adventure even if it’s quite far from being the book on screen. Of course, part of that might be more due to the film’s massive critical and commercial failure.

By 2008, it was about the crest of fantasy adventure films in the early 2000s. I suppose describing it as such is perhaps misleading, as most of them weren’t especially successful, instead largely being a bid to ride the coattails of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings adaptations (2001-2003) and the long running series of Harry Potter films (2001-2011), both of which sent studios scrabbling for similar properties to cash in on. The most (in)famous of these probably being The Chronicles of Narnia (2005-2010), which I guess has the distinction of being one of the few successful enough to get multiple films before the plug was pulled, and The Golden Compass (2007), an abortive attempt at filming the His Dark Materials books that got chopped about significantly in post because I guess New Line didn’t bother looking into the themes of the thing when they bought the rights, though God knows there were others. While it’d be easy to put Secret of Moonacre in the same sort of category (because, really, it probably was intended to capitalise on such things; the fact that Little White Horse is well documented as being one of J.K. Rowling’s favourites and a professed inspiration probably helped), it’s kind of an odd one, as unlike the bulk of them it’s based on a single book and so has no real easy franchise potential and despite rewrites still finds itself with a very definite conclusion with pretty much everything wrapped up nicely. No sequel hooks here.

One ponders why this particular film seems to have attracted the particular ire of critics and audiences, god knows there are worse of its type, though I can theorise. The film is especially child friendly for one, and it’s especially girly for another. Frankly, neither of these are bad things really. It feels like there’s a real dearth of U rated material coming out these days, with most of it either being things aimed squarely at the tiniest of children (wow, they release a lot of compilation films of Paw Patrol and Peppa Pig) or classic lit adaptations that are unlikely to be of much interest to kids. Sucks to be you if you have, like, a five-year-old and want some kind of media to watch with them that doesn’t make you want to claw your eyes out, I guess. This child friendliness does extend to the plot, which isn’t especially risky and has a large element of good moral fortitude with its heroine who is always good but never a goody-goody and an outright stating of the subtextual message at at least one point just in case any children didn’t notice. The sort of thing referred to by Children’s Film Foundation way back when as “intimacy with good example”. The whole thing does feel in some ways reminiscent of CFF fare, though I expect that may be because of my recent excursions into the catalogue skewing my ideas of child targeted media rather than anything else, as it actually violates quite a lot of their standard tenets, not least having only one actual child as well as a whole heap of flatus that definitely wouldn’t fly. Also, there’s not a big slapstick chase as the climax. That was like the law or something. Anyway, at the same time, it’s unusual for a film of this type to resolve itself in such a non-actiony way which this very much does; you have action leading up to the climax (as well as, oddly, in the denouement) but it refrains from actually solving the central conflict of the story with any conventional action scene. Even when the two houses come face to face, things are kept low key.

As for the girly thing, well… things targeted towards women, and in particular girls, are invariably deemed as having less merit regardless of actual content. It’s like society is inherently sexist or something. It all has a long history.

This is the second live action film by animation type Gabor Csupo, who is probably best known for being co-creator of Rugrats (1991-2004), and also seems to have pretty much killed his directing career; he’s made a grand total of one film since this one, nearly a decade later with a much smaller budget and aimed squarely at the Hungarian market. It seems like rather a comedown. One presumes that this is due to this thing’s failure. Despite being quite tightly budgeted for this sort of film (purportedly in the region of US$27m), it nevertheless didn’t come close to recouping the production costs. Unfortunate really, as there’s quite a bit to like here. The production design is quite lovely, for one thing, managing to create a tangible feeling world with a certain degree of subtlety in its approach to its fantasy. While it has lavishly designed environs and wardrobes, for the most part it doesn’t spend its time calling active attention to the magical setting. It’s not always on, with much of the wonderment being at eccentric and curious yet entirely feasible elements of the estate. While things aren’t always magical, there’s always something just casually off about everything, enough to be aware that things are going on; magic in the ordinary and all that. Unfortunately, it manages to break this spell whenever the cook (Andy Linden) shows up, a character whose behaviour is so overtly and conspicuously magical, and so early in the film, no less, that it feels entirely at odds with the rest of the film and ends up giving the sense of executive meddling, as if someone on high decided that odd thing, such as the dog being a lion in the mirror or the stars painted on Maria’s ceiling falling, just wasn’t enough for the kids. We’s gots to have a wacky teleporting chef who pontificates about magic being restored to the house. Hmm.

The film’s reluctance to outright have one of the sides be in the wrong and the other in the right is perhaps commendable, though it doesn’t necessarily do it very well, with the De Noirs tend to be inherently portrayed as more villainous than the Merryweathers pretty much regardless of the circumstances. I suppose it’s not entirely unfair, because, you know, they’re meant to be brigands, but outside of being informed of the Merryweathers’ own corruptibility we don’t see all that much of it beyond the odd calling out of Sir Benjamin’s woman hating.† In fact, the one time it does delve the problems with the family, it decides to go a bit too much into its both-sides-ism; the script tries to pin the failure of Sir Benjamin’s engagement (that results in his misogyny) on both him and his erstwhile fiancée (Natascha McElhone), and the whole issue could be sorted out by putting pride aside and apologising to each other when… no, she very much isn’t at fault in the situation as portrayed and has nothing to apologise for. I suppose it could be a hangover from an earlier draft; the failed engagement is an element of the book, I believe, and their falling out in that is over something a lot more irrelevant to the overall plot. It leaves a bitter taste, especially with the otherwise fairly decent portrayal of the heroine. Maria manages to be an active and adventurous protagonist while still being treated very much as feminine, as opposed to the standard route of having her be a tomboy who eschews the girly (obviously not that there’s anything wrong with that either, but it’s rare for pretty much a film of this type to not try to make its female protagonist more masculine). It’s perfectly willing to have her take charge of the adventure while also having her be into pretty frocks and needlepoint and other typically feminine accoutrements and activities, and it doesn’t expect her to shed them in order to be the hero. Her interests and appearance are immaterial to what makes her heroic. It’s also good enough not to make her utterly impervious.

There’s a weird subsection of children’s films that don’t really perform at the box office, but go onto be viewed fondly and nostalgically by the people who grew up with them because they’d get trotted out on TV of a rainy Saturday afternoon or they’d be hovering around rental shelves or such. The modern equivalent I guess is some of the oddities that turn up on Netflix et al. There’s a certain level of fun to be had in guessing which these films will be in the future. This kind of seems like it should’ve been a shoe-in for that, but it doesn’t seem to have really happened; while there are certainly Gen Z types on Letterboxd who seem to have fond memories of the film, it hasn’t really pierced into that weird semi-obscure childhood favourites category, and doesn’t seem terribly likely to at this juncture. I suppose it was released at the wrong time; video rental shops were on their way out and streaming services hadn’t really come in yet; though it somehow doesn’t seem to have made the transition to weekend/school holiday TV regular fixture or onto Netflix or Amazon Prime as some kind of catalogue package deal. I’m actually not sure I’ve ever even seen it on TV listings at all, which is all very surprising and weird. It’s too bad. While it’s not some marvellous hidden masterpiece; there are bits that definitely don’t work; it more than serves its purpose, has some distinctive quirks that make it stand out from the competition, and is generally an all-round wholesome and pleasant affair.

† This is at least better than the novel, I guess, which seems to treat misogyny as a mostly harmless personality quirk rather than a massively toxic character flaw and societal ill.

At time of writing, The Secret of Moonacre is available to rent off of Amazon, amongst other services. I recommend JustWatch for keeping up with where films are streaming (including this one!). Alternatively, physical copies are reportedly available for rent via Cinema Paradiso.

The film presently has a U rating (last being submitted in 2009), with the BBFC citing "very mild threat and language".