Sleepwalker

A horror movie for the '80s. …and the '90s. …and the 21st century. God, I'm depressed.

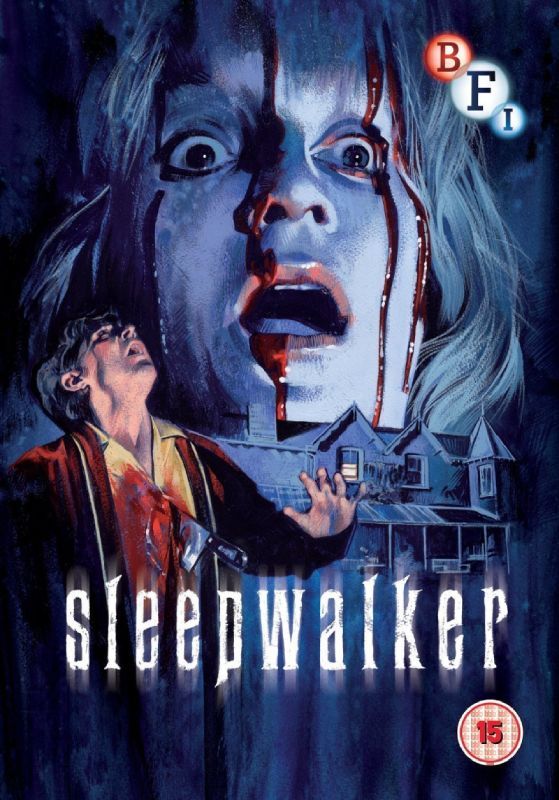

UK DVD cover | British Film Institute

1984 — UK

A presentation of METRO CINEMA and ROBERT BREARE for BIOSCOPE

Cast: BILL DOUGLAS, JOANNA DAVID, HEATHER PAGE and NICKOLAS GRACE

Direction and Production design by: SAXON LOGAN

Producer: CHRISTOPHER SPRAGUE

Executive Producer: ROBERT BREARE

Screenplay by: SAXON LOGAN, JOHN VARNOM and MICHAEL KEENAN

Editor: MIKE CROZIER

Music: PHIL SAWYER

© Bioscope Ltd

No trailer for this one. Not just 'I can't find one'; it almost certainly doesn't have one. Hell, why do you think I've got the DVD cover rather than a poster? This isn't the sort of film that got marketed.

The ‘80s! Greed was good, and all that shit. The decade and its prevailing ethos frankly left the world in a terrible state from which it’s never really recovered. Having any sort of concern about it was considerably less popular. I’d say ‘it’s looking like we’ll be getting back to that soon enough’, but, really, we already are. Any disagreement or concerns about the direction of the country is doing it down.

1982 saw the release of Britannia Hospital, directed by Lindsay Anderson, best known for if….. The film continues the exploits of if….’s protagonist, played by a returning Malcolm McDowell, and follows the goings on at the eponymous hospital. A new wing, headed by an unscrupulous scientist, is set to be opened that day by the Queen Mother, meanwhile the kitchen staff are on strike, people are protesting the hospital’s treating of foreign despots in its private wing, and an investigative reporter has snuck into the hospital to shoot an expose on its dubious practices. It’s all an allegory for the state of Britain, and it went down like a lead balloon at home, with people even finding the poster for the film offensive.

Why, if this is meant to be about Sleepwalker, am I talking about an entirely different film? Scene setting. In Sleepwalker, Alex and Marion Britain (Bill Douglas and Heather Page, respectively) have recently inherited a house, ‘Albion’. The house is quite old, and it’s in fairly a poor state of repair. To this house, they’ve invited their friend Angela Paradise (Joanna David) and her husband Richard (Nickolas Grace), an upwardly mobile couple, to dinner. (It's hard to spot, so I don’t know if you noticed, but there’s actually some allegory going on here.) Things go badly; friction arises between Alex and Richard pretty much immediately, while Marion gets pissed as a fart, puts the moves on Richard, and starts to discuss that one time when Alex tried to kill her in his sleep. Angela, for her part, just kind of simpers. Later on, wouldn’t you know it, someone’s laying waste to the people in the house.

Jokes about the subtlety or lack thereof aside, there is certainly something to ponder about the film as a film. While the thing works as an allegory, I’m less convinced that it works as not-an-allegory. Its brief runtime does not really allow for the time to really get to know these characters, so they’re characterised in rather broad strokes. To be fair, there’s nothing inherently wrong with something being all allegory, all the time. Frankly, it’s not often something really commits to having everything map. Perhaps for that reason, I’m fond of Animal Farm, the novel at any rate (the film… eh, no, not really), which is pretty damn open and consistent about its being the rise of Stalin with farmyard animals. It’s typical place on the curriculum makes sense as it’s a convenient introduction to the entire concept of allegory. Compare, say the Narnia books which do not all map neatly onto the Christian doctrine that runs through the things thematically (granted C.S. Lewis flatly claimed they weren’t allegorical, despite being chock full of allegorical elements, due to a combination of that and not being originally conceived with the intent of it being allegorical; Lion-Jesus happened all on its own apparently, which I guess says some stuff about Lewis). Of course though, they’re novels and have a lot more room to flesh out their casts. Sleepwalker has a slight run time, but even full-length films ultimately have less space to work with than a novel typically does. It’s notable that 2017’s mother! (a film I've heard amusingly described as “the rare modern movie that is just oops-all-allegory”), for instance, keeps the specifics surrounding its characters rather vague, increasingly so as the thing goes on. However, while Animal Farm and mother! (and I suppose The Chronicles of Narnia) are allegories for specific narratives like the Russian revolution or the Bible or whatever, Sleepwalker has the difficulty of, er, not doing that, in favour of straight up satire of the state of society and where it was apparently headed. Like Britannia Hospital, see? Though perhaps even more pessimistic.

As such, naturalism is thrown to the wind. The characters represent ideas and concepts, rather than being people. That the men represent the socialist and the neoliberal should be plainly obvious to anyone, though what the women represent is somewhat less immediately apparent; the official explanation from Saxon Logan is that Angela represents the middle class and Marion is ‘Britannia’. It lines up, though it does make it seem like both Marion and the house represent the nation. The house is falling apart, and for all Marion’s chiding, Alex isn’t really preventing it; between her, the house and his own work, there’s too much to do all at once, even ignoring his losing himself in reverie. Marion instead tries to hitch her wagon to Richard, who’s making a killing in business by pretty much any means, including through transparently unscrupulous ones (his business incidentally is video, which seems hilariously ‘80s). He’s happy to accept her attentions, but welches when the time comes to give back. Angela’s deal in all this is that she’s largely disapproving of her heinous husband’s behaviour, opinions, all of it, and rather more sympathetic to the problems around her, but is unwilling to actually rock the boat; she’s getting far too much (material) comfort out of the current arrangement to really want to do anything about it. She’s also the sort of person to have false nostalgia for the Victorian era, or rather what she imagines it to have been.

In keeping with the non-naturalistic style, the film is shot through with an indigo hue. While obviously this serves a similar function to the old and eminently mockable ‘blue filter equals night’ seen many an old horror film, however it lends a different feel. The shade of blue is more vivid, more reminiscent of the nightmarish colours of Brian de Palma or myriad giallo films. Instead of regular light run through a slightly blue filter, the actual light source appears to be this colour in the scenes set in the dark, giving the whole affair an off feeling, a moonlight gloom.

A further part of the reason for that Britannia Hospital bit earlier was Logan’s position as a protégé of Lindsay Anderson. This is highlighted in the film’s use of politics and in its rather scabrous satire akin to the Mick Travis films, with a focus on the ideas at play rather than naturalistic storytelling (if… was apparently the film that got Logan into filmmaking as an art form). The key inspirations for the work include Anderson’s Britannia Hospital, a film that I’ve mentioned a bit too often at this point in the review, and James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932) (along with Hammer films apparently, though that seems a bit more of a generic Gothic film point rather than anything specific). The Old Dark House is an interesting point though. Whale’s blackly comic ‘haunted’ house film (the inverted commas being because the terrors of the eponymous house are quite earthly) is typically deemed the basis for that particular sub-genre of horror film. Based on a novel by J.B. Priestly, the relationships and goings on similarly function as metaphor for changes in and disillusionment with society in the wake of the Great War, as the stranded tourists find themselves in a strange crumbling home which holds a deadly secret that may well be a stand-in for the human condition. The film (reportedly more than the book) plays the bizarre goings on for uncomfortable laughs as much as hilarious chills.

Also like The Old Dark House, Sleepwalker managed to get lost for a bit. Whoops. Its appearance coincided with considerable changes in the British film industry. While the thing had apparently played quite well at the Berlin Festival, as what the BFI refer to as (daftly) a ‘long short feature’ (essentially clocking in at over 40 minutes, but not long enough to be a main feature), it was unlikely to see much sales on its own, but by the mid-‘80s the market for such things was on the wane following a general decline in ticket sales. The repealing of the Eady Levy didn’t help matters,* and so the perhaps already predisposed distributors were unwilling to touch it. And so it pretty much died and disappeared, until some fourteen years later, film critic and fashion-don’t Kim Newman went and discussed it a bit in an issue of Flesh & Blood, prompting interest and incredulity on the internet that such a film could exist and disappeared without a trace, with the implausible cast list and made up sounding name of the director leading to the suggestion that it was actually a joke. Then the director turned up to one of these naysayers and was all ‘nope, it and I are real’. So, that’s a fun story.

The film perhaps doesn’t entirely work. Where Logan stands is quite well established; with little time to waste, the character whose viewpoints are wrong (it’s Richard, obviously) ends up feeling so cartoonishly awful that the only other thing it could do is go all Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure and have him violently kill a dog on screen.** Of course though, I’m too young to remember much of the ‘80s, especially the decade at its peak; perhaps the film’s portrayal is less cartoonish than it appears. This is perhaps just a grumble however, as, for everything, the film is quite densely packed.

Regardless, the central heart of the film remains relevant today, but it seems bleaker with every passing minute.

*Ostensibly, the idea of the levy was that a proportion of the box office for registered British films would go to producers, though seemingly in practice distributors would arrange the business end to get at least a cut of the pay-out. The Orchard End Murder (1981) runs for some 50 minutes and was reportedly one of the most successful British films of the year; the distributor bought it outright and attached it to an easily sold American headliner film. As that wasn’t eligible for any cut of the ticket sales, from what I can tell all that sweet, sweet Eady money went into said distributor. The removal of this dubious shortcut presumably hastened the long short’s demise.

**Araki's figured out the ultimate way to establish to the audience that CHARACTER BAD.

At time of writing, Sleepwalker isn't even listed on JustWatch and doesn't appear to be on any major streaming service. Sorry, kids. Usually it seems that the BFI get digital rights to films they release on video, but not this time apparently. Alternatively, physical copies are reportedly available for rent via Cinema Paradiso. (In case you're leery about the idea of renting the disc of a 50 minute film, the release comes with a bunch of other shorts.)

As of 2013, the film, as you can see quite easily from the picture, is a 15 with the BBFC warning of "strong violence and strong language". Despite not succeeding in finding distribution back in the day, surprisingly it was actually rated at the time (as an 18).