An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

Although there is no change to my patrician façade, I can assure you my heart is breaking.

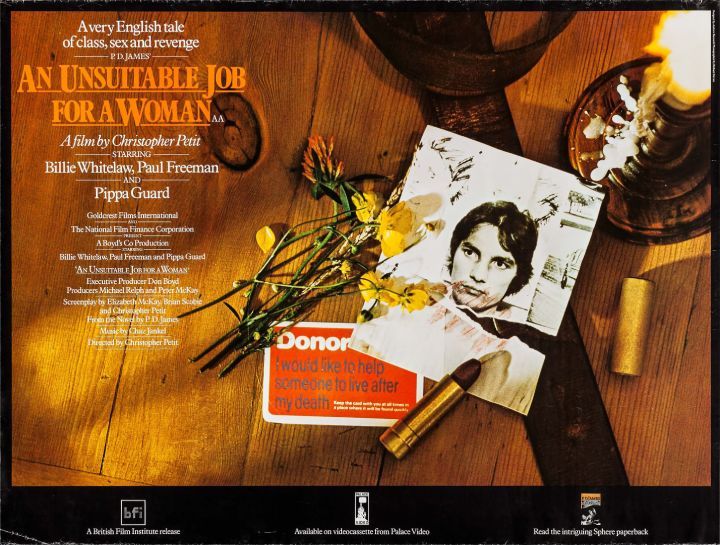

UK poster | British Film Institute

1981 — UK

A BOYD'S CO. production, presented by GOLDCREST FILMS INTERNATIONAL in association with the NATIONAL FILM FINANCE CORPORATION

Cast: BILLIE WHITELAW, PAUL FREEMAN and PIPPA GUARD, with DOMINIC GUARD, ELIZABETH SPRIGGS, DAVID HOROVITCH and DAWN ARCHIBALD

Director: CHRISTOPHER PETIT

Producers: MICHAEL RELPH and PETER McKAY

Executive producer: DON BOYD

Screenplay: ELIZABETH McKAY, BRIAN SCOBIE and CHRISTOPHER PETIT

Original work by: P.D. JAMES

Editor: MICK AUDSLEY

Cinematography: MARTIN SCHÄFER

Production design: ANTON FURST

Art direction: JOHN BEARD

Costumes: MARIT LIEBERSON

Music: CHAZ JANKEL, PHILIP BAGENAL and PETE VAN-HOOKE, with MARK ISHAM

© Carolina Bank Ltd

No trailer for this one that I could find, though the BBFC listing seems to confirm that Palace did cut one for their video release. (Update – 01 Dec. 2021: Not anymore they don't; it's disappeared from their page on the film. How mysterious.)

You want to know what I like? Of course, you don’t, but I’m going to tell you anyway: those recent BBC adaptations of Agatha Christie novels, those ones that are moderately controversial amongst ‘purists’. The complaint is supposedly due to them not being hugely faithful to the source material, which, you know, fair enough, except these people only seemed to come out of the woodwork for the BBC’s recent run, when ITV’s string of adaptations went off-piste an awful lot of the time as well. I assume the real issue for these people is the ditching of the cosy murder mystery stylings of ITV’s Poirot (1989-2013) and Marple (2004-2013) runs (or indeed the BBC’s own old Miss Marple series (1984-1992), but, let’s be honest here, the ‘cosy murder’ sub-genre of detective shows is very much ITV’s wheelhouse) in favour of a more gothic and sinister tone.

Also, the original ending of Ordeal by Innocence is the perhaps the most tritely obvious way it could conclude.

Anyway, “what does this have to do with a slightly obscure adaptation of a P.D. James novel?” I like to imagine you’re asking, even though the clues are probably pretty obvious. Well, I’ll get to that in a bit.

Cordelia Gray (Pippa Guard) works for or with (depending on who’s asking and when) Bernie Pryde, a private investigator. Unfortunately, one day she gets to work only to find him quite dead, apparently at his own hand. On the day of the funeral, a woman, Elizabeth Leaming (Billie Whitelaw), shows up, apparently expecting a meeting with Pryde on behalf of her boss, property magnate James Callender (Paul Freeman). Despite Ms Leaming’s dismissal of the prospect, Cordelia convinces her that she’ll take the meeting on behalf of her late ‘partner’. It seems that the Callender family’s lone son, Mark (Alex Guard), has hanged himself. Everyone seems able to accept that that’s what happened, but the mystery they wish to hire Cordelia (or rather her late boss, but needs must and all that) to solve is the question of why he did it. Cordelia accepts, but her eagerness to prove herself soon seems to turn into obsession.

There’s an obvious joke about the amount of the Guard family that are in this film. Everyone’s made it already. Well… ‘everyone’ is perhaps a generous word given the film’s semi-obscurity.

This is apparently very loose as adaptations go. A look at the Wikipedia page for the novel sort of supports that claim (and those familiar with the book will likely spot at least one difference in that summary above), with the film keeping the basic set up and some key beats of the mystery, but chopping and changing a bunch of the in-between parts (and also cutting an appearance by James’ pet character, Dalgliesh, entirely). As such, fans of the novel seem understandably put out. I haven’t read the novel (or any of P.D. James’ work, for that matter), which is perhaps for the best. The rather pat plot summary that Wikipedia supplies seems to suggest a fairly standard bit of detective fiction in form with the ‘novelty’ of having a female P.I. I suppose having a woman sleuthing in a professional capacity rather than engaging in purely amateur shenanigans was probably different in itself in 1972, though a cursory look seems to suggest it wasn’t really all that new as a concept in and of itself. Nevertheless, Cordelia Gray has seemingly become one of the big characters in detective fiction, at least within the fandom, despite there being only two books (a decade apart) in the what-gets-generously-termed-as-being-a series and it seeming like everyone hating the second one from what I can tell. As I say though, I haven’t read any P.D. James; while the novel’s plot as dryly summarised by whoever it is who wrote the Wikipedia page seems pretty meh, one assumes that her own prose is rather more effective and interesting in how it puts the story forward. She presumably didn’t get to be held in such regard while being sloppy at her craft. (I mean, it does happen, such as J.K. Rowling’s cringeworthy prose which only got worse when her editor apparently stopped giving a shit because people will buy anything Harry Potter anyway even if it does balloon to three times the length from being stuffed with extraneous and interminable side plots that don’t really go anywhere.)†

The general consensus of the film seemed to be that it was too arty for a mainstream film and too mainstream for an art film. An odd predicament to be in perhaps, although I wonder if that would’ve still been the case even just a few years later. Monthly Film Bulletin suggests there was quite a bit of interest from some major independent distributors prior to its premiere at Berlin, where it had a fairly poor response which caused said interest to die away. Admittedly the finished product seems like an odd film for the big names to want in on, although EMI was going through a weird phase at the time where they were getting into some strange and rather uncommercial seeming British projects, such as Britannia Hospital (1982) and Memoirs of a Survivor (1981), seemingly to avoid (futilely) the insinuation that they weren’t interested in the local film industry so much as their ventures into quasi-American films or the ultra-safe bet exports like their Agatha Christie adaptations. Maybe they thought it’d be something more like the latter? James was apparently deemed the successor to Christie’s throne. In the end, it was sold to the fledgling Channel 4 as part of their initial slate of films and released in cinemas, along with some of their other early films, by the BFI itself; it is certainly in keeping with some of the projects that the channel was involved in.

I kind of feel the need to go into this history, largely because there was this vague mystery as to how this ended up part of the Film4 catalogue when there didn’t seem to be any information on their involvement out there (there’s a throwaway line in the Autumn 1982 Sight & Sound where producer Michael Relph says of the film’s market performance that it’s “too early to say, although the sale to Channel 4 will help towards recouping the cost” (Moses, 263), this happened after the film was finished we can assume, as John Pym’s useful survey of Channel 4’s ‘80s film output which only covers stuff they either helped develop or bought into during production makes no mention of it, despite having a wealth of films that don’t mention their involvement), and also because a lot of sources on the internet seem to think this was a TV movie, a BBC one no less. It seems unlikely that the BBC would have been willing to go this sort of route if they had adapted it in the early ‘80s (or that they’d have shot it on film, for that matter, and they DEFINITELY wouldn’t have used the 35mm that this reportedly does). Mind you, Americans seem to think all British TV is the BBC. (With that said, at least one of the things I looked at that said as such does seem to be from a British site.) That’s all moot anyway, as this was, by contemporary accounts, very much a theatrical film.‡

With that preamble, what’s the film’s deal? Why would it see such a tepid reaction in its day? Well, obviously not having been there, I can’t definitively answer that second one, but I can speculate wildly and dangerously! For what is ostensibly a detective story, the film isn’t entirely interested in the detective side of it. While Cordelia goes about her business looking into the case, the film never sees fit to draw attention to the clues as to the truth of the case. This is in keeping with director Chris Petit’s previous work, Radio On (1979), also ostensibly-but-not-really about investigating a suicide that mightn’t be one, though Unsuitable Job is less opaque than that film overall. Unlike the earlier film, it does present a solution to the mystery, though unlike the standard mystery film it does not provide a definitive answer as to whether Cordelia’s solution is actually correct. The clues are there, as I say, for you to potentially draw the same conclusions as her, but the film isn’t going to actively highlight them, it’s not going to elaborate on the hows and whys, and it’s definitely not going to make you privy to her thought process. One imagines the film’s reticence to provide easy answers, refusing to even comment on whether justice has been served, did not endear it to mainstream audiences. The content wasn’t for the mainstream, the package wasn’t for the arthouse (though the aforementioned snippet of Relph talking of the film’s performance has him as saying that the critical reception was “[v]ery good by critics of fringe publications” though “not so good by establishment critics” (Moses, 263)).

This was apparently supposed to be Petit’s attempt at breaking into mainstream filmmaking. While Radio On enjoyed some success, people weren’t really queuing up to give him more work, the local film industry being in another downturn, so he went looking for something more saleable to pitch, with mystery stories being “the only internationally marketable product” (Sinclair, 313). The landing on An Unsuitable Job for a Woman coming about due to the female detective (who is not an establishment figure (Petit, 120)) and his finding it “kind of a gothic story of a haunting – rather than just a straightforward policier” (Sande). This is reflected in the film, wherein it becomes “a story of strange, buried passions in which everyone either haunts or is possessed” (Petit, 120). It’s curious to see a film where the specifics of the mystery manage to be quite so immaterial, though it seems like that was something that occured not infrequently in the less mainstream end of early '80s cinema. The focus is less on the mystery itself, so much as those left behind. It’s quite haunting and discomforting in its portrayal. It’s also has a kind of melancholic beauty to it.

The idea of filming an English murder mystery story came during a drive through the Cotswolds whose quaint, orderly, ‘typically English’ villages and towns called to mind George Orwell’s remark that the main motive in English murder was for respectability. Only the English could get their priorities so hopelessly wrong.

Petit, 120

While we get into the requisite heart of the ‘80s; Cordelia glibly sums up Callender’s business, itself quite the opposite of the novel, as “making money”, and there’s very much a ‘Britain on the precipice’ air to the central conflict; the story also functions as a study of repressed emotion, with the two sides feeding into one another. Emotions are as closely guarded as any of the secrets that Cordelia is trying to uncover. The deep-seated malaise at heart of everything is born of this denial of emotion. If there’s one thing that the British have historically loved it’s the vague concept of respectability, and few things are as respectable as wealth and success, while few are as embarrassing as the outward expression of emotion. Eventually however something has to give, and by the end of the film just about all the major players have popped their corks. Cordelia is presented as a more warm and openly empathetic figure than the remainder of the dramatis personae while remaining caught up in societal expectation. For all this, my vague skimming of the novel suggests the film version to be a more closed off and reserved character overall, beyond simply no longer having access to her thoughts; this is evidenced early on in the aftermath her to finding Bernie Pryde’s corpse, with her informing the typist so:

[Cordelia] put her head round the office door and said quietly:

‘Mr Pryde is dead; don’t come in. I’ll ring the police from here.’

James, 6

Compare the film, wherein she sits down at her desk while the typist whitters on about her new nail polish, before simply saying that she (the typist) may as well go home, because there’s no work today. Her comparative empathy leaves her susceptible to the case’s quasi-haunting and possession which comes as a result of her own unresolved issues surrounding her mentor’s suicide. She becomes blurred with Mark Callender, her mentor with his father.

Much of the film is shot in a moody chiaroscuro palette, with its Berkshire countryside locations taking a sinister air. Part of this would appear to be making the best of a bad situation; Petit brings up quite a bit his desire to have shot in the Fens (while studiously avoiding Cambridge itself, a major location of the novel), but the budget wouldn’t make it that far, only as far as the home counties, “surely the least cinematic part of the entire island” (Petit, 120). I ponder if such a statement is exactly true, given as Powell and Pressburger managed home counties location shooting in Black Narcissus (1947), but that’s beside the point really. Even if they aren’t the locales envisioned, they nevertheless have been imbued with a sense of gothic foreboding, enhanced by the film’s long periods without dialogue and its soundscape of ambient noise; birds and weather and children laughing in the distance.

I’ve seen reviews link the film’s manner and aesthetic to the mystery films of Jacques Rivette, which, perhaps. Its elliptical mystery, gothic tones and themes of obsession and respectability reminded me more though of Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) (Petit, for his part, claims Fassbinder was the intention however). Pippa Guard cuts a wan, waifish figure in the darkness, exuding a sense of otherness that distinguishes her from the hard nosed people with whom she interacts. She plays Cordelia at once warm yet distant, relying heavily, as is the film’s wont, on physical acting to convey her state of mind, her emotions, her logic, and managing admirably. (One is perhaps obliged ethically to disclose that I have met Pippa Guard a couple of times in capacity as a student; I don’t really remember much so I don’t really have any impressions (I assume the inverse is even more true). I’d like to imagine it hasn’t caused any sort of bias.) And, yes, she really does only get third billing despite being the lead character and being on screen for nearly the entire film. The casting of multiple family members, mocked though it may be (no, I don’t think it was budgetary, I doubt the Guard family came on some sort of three-for-two offer (hell, one of the ones here has a BAFTA, for god’s sake)), serves to highlight the connection between the characters; she looks enough like her brother for one to draw some sort of link, and the presence of her cousin as another connected character opens up a variety of interesting implications for the story that I’m not going to go into here. The supporting cast fill out their parts well, most prominently with Billie Whitelaw appropriately stern as the steely Mrs Leaming and Paul Freeman patrician as Callender.

Petit is largely dismissive of the film, saying from memory that he’s “sure it isn’t a good film” (Sande). With the levels of compromise involved in its production, including a change in the ending to appease the big name of the cast (why am I playing coy? It was Billie Whitelaw apparently), and his discomfort with the comparatively large scale of the whole enterprise in comparison to his earlier (and seemingly later) work, it’s perhaps understandable, but at the same time I feel compelled to disagree. While it has very definite flaws, it presents a distinct take on the genre, filled with a sense of pathos that is typically missing from it. The major plot beats of the mystery are perhaps obvious, but that feels beside the point, as the film’s greatest storytelling asset is in its implication and what’s left unsaid.

James herself was apparently diplomatic about the whole thing, with Iain Sinclair claiming that “Dame Phyllis, reeling out from a viewing, was heard to remark, with characteristic charity, that she felt “it was the director’s film”” (Sinclair, 315), which is at least not as bad as her remarks regarding a later take on her work; Cordelia Gray eventually hit on the inevitable fate of all detectives in fiction, an adaptation for ITV, that James despised for the liberties it took to such a degree that she supposedly stopped using the character altogether as a result (Independent (a))… ignoring the fact that she barely used her anyway.

† And don’t try and give me that ‘they’re for kids’ crap, because a) her adult targeted fiction is written in the exact same voice, and b) children deserve better than a ‘so what?’ attitude when it comes to media.

‡ At this juncture, it seems that it wasn’t permissible for BBC productions to be have theatrical releases, owing to established union type stuff; Antoinette Moses’ survey of British film production in 1981 discusses it in relation to Colin Gregg’s then forthcoming adaptation of To the Lighthouse (1983), a BBC co-production that was to be sold theatrically abroad (Moses, 266), an apparently unprecedented move. The first film theatrically released in the UK that the BBC (co-)produced was reportedly 1989’s Dancin’ Thru the Dark (Pym, 9), although the BFI claim they were involved in the production of Herostratus (1967) (J.A.D., 87).

At time of writing, An Unsuitable Job for a Woman does not appear to be available to rent off of any major services. It is however available to stream via both BritBox's own service and their sub-channel on Amazon. I recommend JustWatch for keeping up with where films are streaming (including this one!). While Cinema Paradiso affords the film a page (because I specifically asked them to add it), there is not presently a DVD or Blu-Ray release available in the UK. (Update – 01 Dec. 2021: A 4k restoration for a Blu-Ray edition has been announced for release in February 2022.)

The film presently has a 15 rating (last submitted in 1991), predating detailed info on the BBFC website; prior to this, it had an AA rating, which was more or less equivalent. For the most part, there's not all that much that seems likely to upset too much, but with that said I wouldn't be terribly surprised if it were to be upped with resubmission; there's a fairly lengthy and detailed hanging scene (including making a noose) that they'd likely take a dim view of under their current standards. Beyond that, I don't know, there's a brief bit of toplessness.

(Update – 01 Dec. 2021): The BBFC have since updated the page. While it doesn't have a pithy one-line description of the content that netted it a 15, it does have the detailed stuff: the categories elaborated on are 'suicide' and 'nudity'. So, yeah, plentiful suicide references and imagery, including some bloody detail, and a "short sequence of breast nudity and moderate threat"; one assumes the second part of that sentence is the important bit as she's menaced while in a vulnerable state but not exactly in a sexual manner. Also, yadda yadda infrequent strong language, moderate sex references, jump scare, standard stuff.)

Sources

Clark, R., 20??. 'Unsuitable Job for a Woman, An (1981)', BFI Screenonline. [online] Available at: <http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/587511/> (Accessed 23 April 2021).

Gregory, H., 2013. 'Interview with Chris Petit', The White Review. [online] Available at: <https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/interview-with-chris-petit/> (Accessed 4 June 2021).

Independent, 1999. 'A Tiger in the drawing-room', 22 Oct. [online] Available at: <https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/a-tiger-in-the-drawingroom-743484.html> (Accessed 4 June 2021).

Independent, 2013. 'Man on the outside', 19 Jul. [online] Available at: <https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/man-on-the-outside-27967.html> (Accessed 4 June 2021).

‘J.A.D.’, 1968. ‘Herostratus’, Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1968, 413(35), p.87.

James, P.D., 1972. An Unsuitable Job for a Woman. London: Faber & Faber. (2020)

Jenkins, S.,1982. ‘An Unsuitable Job for a Woman’, Monthly Film Bulletin, May 1982, 580(49), p.93.

Moses, A., 1982. ‘Survey: British Films 1981’, Sight & Sound, Autumn 1982, 4(51), pp.258-266.

Petit, C., 1982. ‘Wanted: A Suitable Job for an Englishman’, Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1982, 581(49), p.120.

Pym, J., 1981. ‘An Unsuitable Job for a Woman’, Sight & Sound, Winter 1981/82, 1(51), pp.40-41.

Sande, K., 2013. 'Coastal Reflections: An Interview with Chris Petit', The Quietus. [online] Available at: <https://thequietus.com/articles/11891-chris-petit-interview-mordant-music-museum-of-loneliness-robinson> (Accessed 4 June 2021).

Sinclair, I., 1997. Lights Out for the Territory. London: Penguin. (2003)